Ninja

Chances are you’ve heard of ninja – the legendary warriors of Japan who dressed in black and attacked in the dead of night with shuriken and poison darts. Well, that’s all rubbish, as is just about everything else you know about ninja. Real ninja (who were also known as ‘shinobi’) were only around for a couple of hundred years, from the fifteenth to seventeenth centuries. Most of what is ‘known’ about ninja nowadays was written down much later, and almost-certainly owes more to fertile imaginations than to reality. That said, ninja did really exist, and they played key roles in some of the most important events in Japanese history.

Japan’s Real Ninja

Ninja were mercenaries who specialized in covert warfare, and were available for hire by anyone who had the means to pay for their services. As such they thrived during the Sengoku (warring states) period of Japanese history, when nationwide government broke down, and Japan was subjected to almost continual fighting between rival warlords. This period began in the mid fifteenth century, and continued until Tokugawa Ieyasu unified Japan under his rule at the beginning of the seventeenth century.

The main role of ninja was scouting and espionage – they would sneak into enemy territory, usually in the guise of priests, monks, entertainers, or other travellers, and collect information on the terrain, the state of the roads, and the disposition of enemy troops.

A komuso monk in Kamakura. Komuso monks travelled widely on pilgrimage, hiding their faces under straw hats to help them to achieve humility. They were adherents of Fuke Zen Buddhism, and they used to be a common sight in Japan. They played the shakuhachi flute both as a form of meditation, and to call for alms. Ninja may have disguised themselves as komuso monks so they could travel freely throughout the country without arising suspicion.

Sometimes they would even infiltrate enemy castles, not only to gather information, but also to spread dissent and undertake acts of sabotage.

While popular culture often depicts ninja scaling castle walls with grappling hooks, and melting away into dark corners to avoid detection, most historical accounts refer to them relying on deception – often by disguising themselves as enemy soldiers.

All of this subterfuge was quite at odds with the samurai code of honour. From the earliest of times, deception and concealment were considered unsavoury aspects of warfare. Even in battle, samurai observed a degree of ritual and decorum – they fought openly and announced their attacks with raucous battle cries. This may explain why ninja emerged as a distinct group – commanders preferred to hire third parties to do their dirty work for them. It could also explain why we know so little about ninja – those in power didn’t really want to acknowledge that they existed, much less that they made use of their services.

Two distinct groups of ninja emerged in the late fifteenth century – the Koga (sometimes Koka) and Iga clans. Iga was a province of ancient Japan, comprising a small plain ringed by mountains. It now forms the western part of Mie Prefecture. Koga was a village just to the west, that has now developed into Koka-shi City in Shiga Prefecture. Mountainous terrain and poor roads made both of these areas inaccessible, and therefore perfect locations for mercenaries to be based. While spying and covert warfare had existed in earlier times, the Iga and Koga clans were distinguished by their specialization in stealth and guile, and were perhaps the first true ninja.

Both clans consisted of several families, each represented by a jonin (literally an ‘upper man’), who was responsible for hiring out ninja. Jonin were assisted by chunin (‘middle men’), while genin (‘lower men’) carried out the actual missions. Historical records reveal little about the every day life of ninja, but they seem to have been recruited mainly from the local farming communities, and to have undertaken training relevant to their special roles. It is sometimes said that samurai, or former samurai who had fallen from favour, became ninja, but there is little evidence to support these claims.

Ninja in War

The first clear record of ninja dates back to 1487, when Iga and Koga ninja helped Rokkaku Takayori of Omi Province to repel the attack of the shogun Ashikaga Yoshihisa. Later, ninja played a key role in helping Tokugawa unify Japan under his rule, ushering in the long period of peace and stability that came to be known as the Edo Period.

In 1560, Tokugawa sent eighty Koga ninja to raid a castle of the Imagawa clan. They managed to infiltrate the castle, set fire to its towers, and kill the castle commander along with two hundred of his men – quite a feat for such a small number of attackers. When besieging Osaka Castle in 1614, Tokugawa sent ten ninja, this time from Iga, into the castle. Their mission was not to fight or destroy the castle, but instead to foster antagonism between enemy commanders – a bold action that must have required great cunning.

A view across Iga Plain. The mountains that surround the plain on all sides helped to protect the Iga ninja from their many enemies.

While ninja may have specialized in spying and infiltration, at times they fought openly. In 1600 several hundred Koga ninja assisted in the defence of Fushimi Castle when it was attacked by forces opposed to Tokugawa, and in 1615 Iga ninja fought alongside regular troops at the Battle of Tennoji, in which Tokugawa finally crushed the last opposition to his rule.

The very last record of ninja involvement in warfare was when Koga ninja helped to crush the Shimabara Rebellion in 1637-38. Peasants in the far west of Japan (what is now Nagasaki Prefecture) rose up in opposition to high taxes and the repression of Christianity by new domain lords put in place by Tokugawa. The peasants were joined by samurai who had been dispossessed by the new shogun.

The rebels made their final stand at Hara Castle, which was besieged by the forces of Tokugawa. On several occasions, Iga ninja entered the castle at night in disguise, gathering information on its defences and discovering secret passwords. When the castle supplies began to run low, ninja entered the castle once again, this time to capture bags of food. Ninja disguised as castle defenders even stole a banner bearing the Christian cross – presumably as a form of psychological warfare.

Eventually the defenders were reduced to eating moss, and the ninja took part in a final assault on the much weakened castle defences. Following the fall of Hara castle, Christianity in Japan was persecuted more severely than ever, but dedicated Christians continued to observe their faith in secret until the prohibition on Christianity was eventually lifted more than two centuries later.

A ninja at Edo Wonderland in Nikko

You can probably imagine that all this subterfuge and warfare didn’t make the ninja universally popular, and it was probably only because of the inaccessibility of their home bases that they survived for so long. In 1579 Oda Nobukatsu, son of the warlord Oda Nobunaga, attacked Iga, but was repelled. Two years later, Oda Nobunaga himself attacked Iga, approaching from six different directions with a force of 50,000 men. This gave him about a ten-to-one advantage over the defending ninja, and this time the attack succeeded. His forces slaughtered many ninja and their families. Those who survived were forced to flee – some sought refuge in the mountains, while others went to work for Tokugawa, one of Oda Nobunaga’s biggest rivals.

Ninja in Peacetime

The lack of major warfare throughout the Edo Period (from about 1600 onwards) meant that there was little demand for the services of ninja. Once the Shimabara Rebellion had been crushed, there was no large-scale armed conflict until the mid-nineteenth century. Tokugawa settled two hundred Iga ninja in the Yotsuya neighbourhood of Edo (present-day Tokyo), and employed them in guarding Edo Castle, the base of the Shogunate from 1603.

Around 1634, Koga ninja also moved to Edo, guarding the castle’s outer gate as well as serving as a police force. Some reports also state that the ninja worked as spies for the shoguns, reporting on the activities of domain lords throughout Japan. Ninja continued to serve the shogunate until the eighteenth century, when Tokugawa Yoshimune (the eighth Tokugawa shogun) dismissed all ninja from his service, and replaced them with men from Kii Province. This seems to mark the end of the ninja era, as there are no reliable accounts of ninja activities after this date.

Assassinations

In popular culture, ninja are often portrayed as assassins, but there are only a few historical references to ninja undertaking such work. One report tells us that a Koga ninja shot Oda Nobunaga twice, using two arquebuses (muzzle-loading guns). Fortunately for Nobunaga, he was wearing armour at the time, and this saved his life. Another attempt was made to kill Nobunaga when he was inspecting Iga Province, after his army had ransacked it. Three ninja fired at him, but they all missed, killing seven of his companions instead. Another report tells us that Nobunaga employed a ninja to assassinate a rival daimyo, but that the attack was unsuccessful.

There are plenty of other accounts of ninja carrying out assassinations, often using ingenious methods, such as dripping poison into their victim’s mouth while they slept. Assassinations like these might make for great stories, but the veracity of most such accounts is very doubtful.

Ninja Manuals

Much of what we ‘know’ about ninja has its roots in one of several ‘ninja manuals’ that were published in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The contents of these manuals ranged from military philosophy and strategy, to detailed accounts of all sorts of weapons and gadgets. Some of the most famous of these are the Ninpiden, dating from 1655, the Bansenshukai (1676) and the Shoninki (1682). While some of these manuals were written by descendants of ninja, they all date from after the time that ninja were active, so it’s doubtful that they were ever actually used in real training.

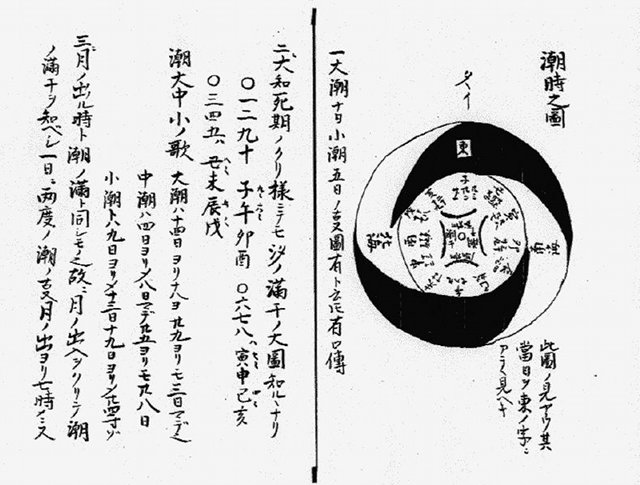

A page from the Bansenshukai ninja manual. This page explains how cosmology and divination can be used to decide on the most opportune time for undertaking certain actions.

The range of specialist equipment described in the manuals is impressive – collapsible ladders, spikes that were attached to the hands and feet to help with climbing, and even rocket-propelled arrows. Perhaps even more remarkable is the absence of firm evidence for most of these contraptions, suggesting that they may have more to do with the inventiveness of the books’ authors than with actual historical practices. It is from books like these that much of the present-day ninja folklore is obtained, such as the association of ninja with shuriken, poison and grappling hooks.

Ninja Legends

It didn’t take long before ninja assumed a prominent place in Japanese popular culture. The folklore surrounding ninja developed for hundreds of years in Japan before ninja were ever heard of overseas, so most of the legends about them are authentically Japanese. Unfortunately the long history of embellishing accounts of ninja has mixed up facts with myth, often making it difficult to distinguish between fantasy and historical truth.

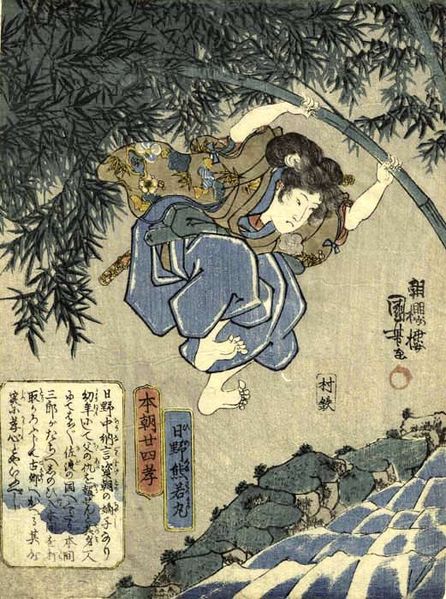

Kumawakamaru escaping his pursuers by swinging across a moat. After his father was executed on the orders of the monk Homma Saburo, he took his revenge. He sneaked into Homma’s room as he slept, and killed him with his own sword. This woodblock print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi dates from the 1840s, by which time Kumawakamaru was widely regarded as having been a ninja.

Storytellers and authors built on historical tales, creating a whole series of legends about ninja’s incredible skills – even going so far as to suggest that they could turn themselves invisible, walk on water and that they had power over animals. Many famous figures from history have also been said to be ninja, but in the vast majority of cases they almost certainly weren’t anything of the sort – the references to them being ninja usually didn’t arise until long after their deaths.

As early as 1680 there are references to kunoichi – female ninja who used seduction as another weapon in their arsenal. In Japanese, kunoichi is written くノ一, apparently because not only are those three characters pronounced ku-no-ichi, they also resemble the three strokes used to write 女 which means ‘female’. There doesn’t appear to be any reliable evidence for kunoichi ever having existed, but this hasn’t stopped them from playing central roles in many supposedly true stories.

Ninjutsu

There may not be much demand for the services of ninja nowadays, but there are active practitioners of ninjutsu – a martial art based on the skills of the ninja, or at least the skills described in the various ninja manuals. The doubtful authenticity of ninjutsu as a martial art hasn’t stopped it from becoming popular – there have been ninja schools in America since the 1970s, and recently ninjutsu has become popular with women in Iran. (Yes really!)

The most prominent school of ninjutsu is Togakure-ryu, also known as the ‘School of the Hidden Door’. It was founded in the 1160s by Daisuke Nishina, and the school’s techniques were secretly passed down from generation to generation, finally reaching Masaaki Hatsumi, the 34th and current grandmaster. He decided to make the martial art public, and began teaching it to students in the 1970s. Or so he says – some people think that he just dreamt the whole thing up himself. I’ll leave it up to you to decide which is more likely.

Ninja Sightseeing

If you’d like to find out more about ninja, or you just want to have some fun, there are several ninja-related places you can visit. Be warned that most of the ninja-themed attractions put more emphasis on the popular image of ninja than on historical accuracy.

Meet Ninja in Iga

If you’re in Japan in the spring, don’t miss the annual Iga Ueno Ninja Festa, which runs from the beginning of April to early May. 30,000 ninja fans travel to the city to see ninja performances, and to get the chance to practice their own ninja skills. All over the town, ninja can be seen walking around, and if you want to join in you can rent your own ninja costume for a day. The city council even holds a special meeting called the ‘Ninja Congress’, in which the mayor and all the councillors dress up as ninja.

A guide at the Iga Ninja Museum removing a sword from its hiding place

If you can’t make the Ninja Festa, don’t worry – the Iga-ryu Ninja Museum is open all year round. It’s based in what is described as a ‘typical ninja house’. A ninja will guide you round the house, showing you all its ninja features. These include hiding places for weapons, hidden exits, a concealed staircase, and even an escape tunnel. An exhibition contains ancient ninja weapons, and over four hundred ninja tools. You can also watch a ninja show that features demonstrations of swords, spears and shurikens.

A visit can be quite entertaining, but while the museum may insist that their artefacts are authentic, you’ll definitely be learning more about the ninja legend than the reality. Even the association of ninja with shuriken (pointed stars and other sharp objects that could be thrown) is very doubtful. Samurai certainly used shuriken, but there’s no reason to believe that ninja used them more than they did any other weapon.

Iga-ryu museum is a short walk from Uenoshi Station, which is about two hours from Tsuruhashi Station in Osaka (¥1,390 on the Kintetsu-Osaka Line to Iga-Kambe Station, where you should change for the Iga Line), or a similar time from Kintetsu-Nagoya Station in Nagoya (¥1,870 on a local train via the Kintetsu-Nagoya Line to Ise-Nakagawa Station, and then the Kintetsu-Osaka and Iga lines as from Osaka). Best of all is that when the Ninja Festa is on, anyone dressed as a ninja gets to travel free on the Iga Line!

Experience being a Ninja in Koka-shi City

Iga’s one-time rival, Koka-shi City, also has ninja attractions. Firstly there is Koka Ninja House, a house that was the former residence of Mochizuki Izumonokami. It is claimed that he was the leader of the 53 Koga ninja families, but this doesn’t seem to be entirely consistent with the age of the house – it having been built in 1703, well after the end of the ninja-era.

There are hidden exits from each room – you need to find them in order to explore the whole house, and there’s a tunnel that leads into the garden. The house contains displays of various ninja weapons, tools and costumes – again of doubtful authenticity. If you really want to get into things, you can rent a ninja costume, and have a go at shuriken throwing. Koka Ninja House is about two kilometres walk or taxi-ride from Konan Station.

These girls have just become licenced kunoichi after successfully completeing a training course at the Koga no Sato Ninjutsu Village. Photo courtesy of go.biwako.

Koka-shi’s other main attraction is Koga no Sato Ninjutsu Village, a Ninja theme park that has been running since 1983. The park is surrounded by forest, which is meant to create the atmosphere of a hidden ninja base. It contains the Koga Ninjutsu Museum, with another display of Ninja paraphernalia, and the house of a Koga ninja descendant that was moved to the theme park from its original location. The big attraction here though is the ninja training site. You can take a course in ninja skills including climbing and crossing water using a ‘water spider’ (a wooden ring). If you complete all of the nine lessons successfully, you’ll be issued with a ninja licence! Koga no Sato operate a free shuttle bus from Koka Station on the JR Kusatsu Line. (If you don’t see a shuttle bus near the station’s north exit, call 0748-88-5000, and they will come and pick you up.)

To get to Koka-shi from Osaka, take the Tokaido-San-Yo Line from Osaka Station to Kusatsu, and then change for the Kusatsu Line. The fare is ¥1,450 to Konan Station, or ¥1,620 to Koka Station which is two stops further on. Either way, the whole journey takes around an hour and a half.

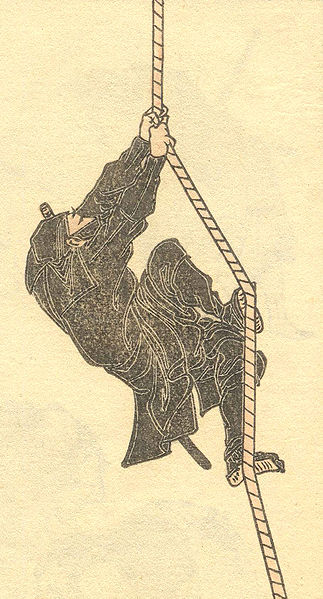

A sketch of a ninja by Katsushika Hokusai. It was published in 1817 as part of the Hokusai Manga, a collection of his sketches that eventually ran to fifteen volumes. This drawing shows that the portrayal of ninja as athletic figures who dressed in black, a representation that remains popular today, was already established at this time.

If you’re coming from Nagoya, take the Kansai Line from Osaka Station to Tsuge (you’ll probably have to change trains at Kameyama, but continue on the same line), and then change for the Kusatsu Line. This way you are coming from the opposite direction, so Koka Station will be two stops before Konan Station. The journey takes about two hours, and costs ¥1,450 to Koka Station, or ¥1,620 to Konan Station.

Ninja Fun in Nagano

Another cluster of ninja-themed attractions is centred around Togakushi Village on the outskirts of Nagano City, the legendary home of the Togakure-ryu school of ninjutsu. The Kids Ninja Village is great for young children. They haven’t let concerns about historical accuracy get in the way of providing the most fun experience possible, so kids can rent a bright-red ninja costume, watch a kunoichi ninja show, and climb and jump around ninja-style to their heart’s content.

Fun-loving adults would be better off heading to the Ninja Trick House and Ninja Museum. There there is the usual collection of ninja artefacts, as well as a climbing wall and a shuriken-throwing gallery, but it’s the trick house that’s the real highlight. Once in the house, you can’t get out again until you find the hidden exit from each room. Believe-me – it really is a lot of fun!

Nagano is around an hour and a half from Tokyo Station by Shinkansen (¥7,770). Take the Zenko-ji Exit from Nagano Station, and then take a bus bound for Togakushi Kogen from bus stop seven. (You can save money by buying a return ticket for ¥2,400.) After travelling for about three quarters of an hour along winding mountain roads, get off at Chusha-miya-mae. From there, both attractions are just a short walk away.

Ninja in Tokyo

The site in Tokyo with the closest association with ninja is probably Sainen-ji Temple. Sainen-ji is the successor to a temple built in 1593 by Hattori Hanzo, a samurai whose family home was in Iga prefecture.

(The original temple

A seventeenth century portrait of the samurai Hattori Hanzo, who worked closely with both the Iga and Koga ninja. It is often said that he was himself a ninja.

was moved to its current location in 1634.)

After the death of Oda Nobunaga in 1582, Hanzo recruited both Iga and Koga ninja to help Tokugawa reach safety in Mikawa Province. His son later commanded the Iga ninja when they served as guards of Edo Castle, and other descendants of Hanzo published ninja manuals. This close association with ninja has led many to regard Hanzo as a ninja himself, and he is often portrayed as such in popular culture.

Hanzo lived the last years of his life as a monk, and his remains now lie in Sainen-ji, along with his favourite spear and his ceremonial battle helmet. The temple is about ten minutes walk east of Yotsuya Station on the JR Chuo Line (9 minutes and ¥160 from Tokyo Station, or 4 minutes and ¥150 from Shinjuku Station).

Hanafuda Kojo Yakei