Battleship Island

Battleship Island is a place so unusual it’s hard to believe it’s real. Over 5,000 people once lived on the tiny islet that’s only 480 metres long and 160 metres wide, making it the most densely populated community ever to have existed anywhere in the world. Now all that remains are the crumbling shells of huge concrete buildings, and a few scattered possessions that were left behind when the island was abandoned. These relics give visitors a few tantalising clues to the island’s history, and what life was like for the people who once called it home.

The remains of the mine can be seen to the left of the picture, with the recently-built walkway for visitors standing out in white. The residential zone is on the right side of the island, with many apartment buildings packed in right next to each other. The only big open space was the schoolyard, at the bottom right of the photo. The hill in the centre is the natural part of the island – most of the rest was reclaimed from the sea in order to make more space for the mine and its workforce.

No one took much notice of Battleship Island, one of over five hundred uninhabited islands in Nagasaki Prefecture, until coal was discovered there in 1810. Even then, nothing much happened until Mitsubishi bought the island in 1890, and began mining coal on an industrial scale. The coal seams themselves lie at the bottom of a 600 metre deep shaft, and extend out under the sea. Japan’s rapid industrialisation led to a great demand for coal, and so to intense development of the island. By 1916 there was such a demand for space that a 9 storey-high apartment building was built to accommodate mine workers – at the time it was the only reinforced concrete building in the whole of Japan, and it’s still standing today. Over time, the island was extended artificially, tripling its total area, and every last bit of space was filled up with everything from mining machinery to apartments, and a school.

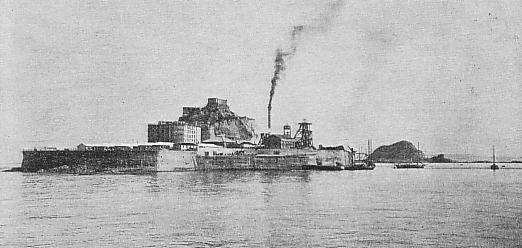

A photo of the island from around 1930, showing the first of the high-rise buildings. Even by this time, the island had been extended well beyond its natural size.

The island’s official name is Hashima (端島), but it’s better known as Battleship Island (Gunkanshima or 軍艦島 in Japanese), because when seen from side-on it bears a distinct resemblance to a battleship. If you see it as a silhouette or in the mist, it’s not hard to believe reports that it was mistakenly torpedoed by an American submarine during the war with Japan, although no one seems able to pin down any hard evidence to back up this story.

Very little of the mine itself remains – mainly it’s just a pile of rubble. The elevated box towards the right of the photo was the entrance to the elevator that took miners deep underground.

In the early days, conditions on the island were very harsh, and many people died from malnutrition, accidents and suicide. The darkest part of the island’s history was in the 1940s, when people from Korea were forced to work in the mine. One former miner described it as a ‘living hell’ – the work was dangerous, the supervisors violent, and there was no way to escape. 122 Koreans died from accidents in the mine during this time, out of a total of more than 200 men who died during the whole time it was operational. Despite this unhappy period, conditions improved after the end of World War II, and Battleship Island developed into a thriving community that was home to workers and their families, including children of all ages. By the time the mine finally closed in 1974, due to oil displacing coal as the main fuel in Japan, many people were sad to leave the close-knit community.

After the last residents left, the island was abandoned for 35 years, until it reopened as a tourist attraction in 2009. By then, some of the buildings had collapsed, and most of the others were considered unsafe, so visitors are restricted to specially-constructed viewing platforms at the end of the island that was once home to the mine itself. The tours have proved very popular, with over 200,000 people a year visiting the island, but they haven’t been enough to satisfy everyone, so quite a few people have found ways to get to the island surreptitiously and explore it themselves.

This steep staircase squeezed between apartment blocks was nicknamed ‘Stairway To Hell’. The island’s residents must have been fit given all the climbing up and down stairs they had to do to get around the neighbourhood.

Local fishermen can obtain licences to fish from the sea wall, on condition that they don’t venture into the interior of the island, but some adventurers have managed to hitch lifts on boats taking the fishermen out, allowing them to explore the whole island. They’ve climbed up half-ruined apartment buildings full of rubble and decaying floorboards, and searched out the few possessions left behind by the former residents. No doubt this was at great risk to themselves, but perhaps we should be grateful, as most of the photos on this page were taken by these fearless adventurers. Some brave souls have even camped out overnight, staying hidden during the day when tour groups are around.

What were once streets are now full of broken wood and rubble that used to be part of the buildings. Here we can see a series of bridges built between buildings, so people could go visit their neighbours without needing to descend to ground level.

By the time the mine closed in 1974, the island had become a self-contained metropolis, with 25 shops, bars, restaurants, a post office, a pachinko parlour and even a cinema. There was a small hospital, which still contains some medical equipment, and an elementary and junior high school, with a theatre and a gymnasium on the top floor. There was very little greenery, but bits of vegetation took root in the few places not covered in concrete, and vegetables were grown on some of the rooftops. The town’s sento with its public baths can still be seen, but it no longer has a roof.

These were some of the best apartments on the island, located on the top of the hill where the mine’s managers lived.

The mine equipment and everything the residents needed to live was jammed into the limited space available, and the whole island was surrounded by a high sea wall, so in some ways it resembles a medieval walled city. It’s hard to imagine what life must have been like in this strangest of towns, where buildings blocked out most of the light and people would have been everywhere. A giant conveyor belt carrying coal passed close to the apartments, and kept going day and night, but kids used to run races underneath it, and play baseball in the few bits of open space. The island also had good connections to the mainland – there used to be 12 round-trip ferry services a day from Nagasaki city, the 19km journey taking 50 minutes, but for most of the time this tiny densely-packed concrete jungle must have been the residents’ whole world. The younger inhabitants would have known no other way of life.

By far the largest open space on the island was this schoolyard. It must have made a very welcome relief from all the claustrophobic alleys and crowded apartment buildings. The building to the left is the school, the first four floors for primary, and the top three for junior high. The low building to the right was the island’s hospital.

The shutdown of the island was planned and orderly, so the inhabitants had plenty of time to pack their possessions and take them with them. As a result, most of what remains is just the empty shells of buildings, with only a few scattered clues about the lives of the people who used to live in them. Here and there we see a rusty old TV set, an old-fashioned dial phone, school books and comics, even pots and pans. Nature is gradually taking back the island, grass is growing up through cracks in the concrete and shrubs are taking hold. Few of the windows have glass left in them, and the narrow alleyways between the buildings are covered in rubble. What’s left gives the impression of a bleak and desolate place, but by all accounts this was once a happy town.

There are very few clues remaining about the people who once lived on the island. These pictures provide a rare glimpse into the life of one former resident.

The island has long been famous in Japan, once being portrayed as ‘The Island with no Greenery’ in a 1949 film. More recently it was the subject of documentaries by the History Channel (‘Life after People’), Discovery Channel (‘Forgotten Planet’) and the BBC (‘Supersized Earth’). It also featured as the lair of the villain Raoul in the 2012 James Bond film ‘Skyfall’. The whole island seems destined to slowly return to nature, but just how long that will take is anyone’s guess.

Battleship Island might not exactly be beautiful, but from high up there are amazing views of the sea and the surrounding islands. This photo was taken in one of the school’s classrooms.

Several operators run tours to Battleship Island from Nagasaki City, including Gunkanjima Cruise, who charge \3,000 for a three hour tour. To guarantee your place, it’s best to book in advance, and in bad weather the you might not be able to land on the island.

When the residents departed, they left very few possessions behind, and the weather has taken its toll on the little they did leave. Here we see the interior of one apartment.

While the residents took most of their possessions with them, the same can’t be said of the school. It remains full of chairs, desks and blackboards. Scattered around you can find everything from an abacus to the remains of a piano. The school was the last building built on the island, in 1958.

Left to themselves, Battleship Island’s buildings haven’t fared too well. Most of the damage was probably due to typhoons that frequently hit this part of Japan.

Apartment buildings were squashed in anywhere they would fit. At one time the whole island must have been crowded with people.

Not the tidiest bit of construction, but there was no space to be spared. Residents on the ground floor can’t have had a very pleasant view, or much light.

This is block 65, the biggest building on the island. It was built in 1945, and its 9 stories contain 317 apartments. The courtyard was one of the few open spaces on the island.

Most of the ceiling in this corridor seems to have ended up on the floor, but structurally the building still seems to be intact.

Space may have been at a premium, but one of the best sites right at the top of the island was given over to this Shinto shrine.

Spaceport Japan Ice Pavilion